Few places seem more intrepid than the Polar regions, the literal ends of the earth that are so remote as to barely appear on a map. Borneo and the Arctic were the two big ones for me this year, and while on paper they could not be more different, the two experiences feel very complementary and connected. Trekking through the jungles of Borneo feels like burrowing deeper into the essence of the earth. It so lush and abundant and just so hot. It makes you feel as if you are standing in the very heart of this planet, at the very center of this rich biosphere teeming with life.

The Arctic (and the Antarctic) is perhaps the last true frontier, the literal and metaphoric limit of life on earth. It is the edge of the only planet that most of us will ever know. Being in the Arctic can make you think about what lies beyond. There’s something very psychologically isolating at being at the very top of the world. Not only is there no human civilization here; it’s impossible to even imagine it. This is not to discount the native cultures that have evolved in these regions for centuries, but eventually you get so far north that even these peoples no longer live there.

That feeling is immensely freeing. On my trip, the furthest north we reached was just above 82 degrees, and our guides guessed that the 20 or so of us on our ship were among maybe a few hundred people that far north anywhere in the world at that time.

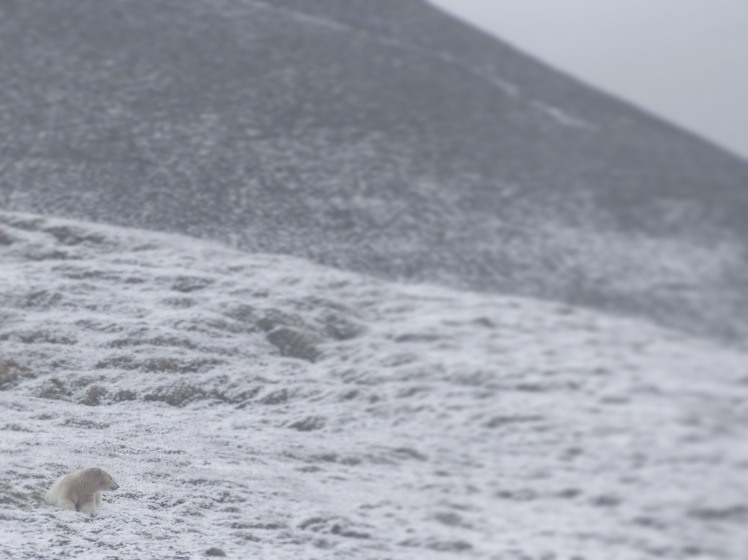

There is so much that makes the Arctic interesting. Of course the conversation almost always starts with polar bears, but some of the other wildlife is just as interesting, to say nothing of the utterly spectacular landscapes. I’ve done a lot of different types of wildlife trips all over the world and the Arctic by far makes you (read: the guides) work for it the most. This kind of trip requires so much patience and a lot of hours bent looking through binoculars hoping to see a speck of white moving across the horizon.

If you’re interested in going to the Arctic, you can do it from a few places. In North America, expeditions out of Canada and Alaska are the most accessible, though trips around Greenland are also pretty convenient if you’re coming from the East Coast. Russia and Norway are the two other countries with territorial claims inside the Arctic Circle. The northernmost parts of Finland and Sweden are technically inside the Arctic Circle, but neither country controls any of the landmasses closer to the North Pole in the Arctic Ocean, so they aren’t really thought of as places to do Arctic Expeditions. Iceland falls just south of the 66th northern parallel, but many Greenland expeditions depart from Reykjavik.

Anyway, accordingly there are several different options. I chose Svalbard mainly because you can cover more ground more quickly. Svalbard cruises tend to be more in the 10-15 day range and within the archipelago, you can experience lots of different landscapes. Expeditions around Greenland and through the Northwest Passage can easily extend beyond 20 days. If I were going to do it again, I would consider a Greenland expedition as there are some animals there you won’t see in Svalbard, but that said I would still readily go back to Svalbard.

Any Arctic expedition in Svalbard (technically a part of Norway, though your passport will be stamped coming to and from the mainland) will begin in the town of Longyearbyen. This is practically speaking the only town on Svalbard, the only exceptions being a few research towns and barely functioning old mining encampments.

I was pleasantly surprised by Longyearbyen. Given how remote it is, there are a handful are pretty good restaurants and hotels and if you’ve forgotten anything, the stores in Longyearbyen probably have a better (and much fancier) selection than whatever outdoor gear store you shopped in before you arrived. Seriously. There’s also a pretty interesting history museum and some very enticing souvenir shops. Some people base their entire trip in Svalbard in Longyearbyen—do not be one of them. If you really want to experience the Arctic, you have to get on a boat.

Ten days at sea might seem like a lot if you’re not a boat person, particularly in such cold conditions, but the seas here are remarkably calm. On my whole expedition, there were only two or three times when the movement of the boat was even noticeable. If you’ve heard horror stories about rough seas in Antarctica, the situation in Svalbard is totally different. Because there are so many harbors and inlets to tuck into around the archipelago, rough seas are not often an issue, particularly if you travel later in the season (end of July/August).

For the most part for this post, I’m just going to feature photos with little text. If you’re just here to see the photos, then I won’t get in the way of that and if you’re thinking about planning your own trip, it won’t be much help my telling you where I went as every ship’s itinerary is different and conditions change so rapidly that two ships out at the same time will not visit the same places. If you have logistical questions about booking an Arctic trip, I’m more than happy to get into the minutiae with you, the different ship options, etc. Please feel free to email me (abbeybchase@gmail.com). Otherwise, onward.

The guillemots have a strange fledging ritual that seems to defy evolutionary logic. Chicks are born on the cliffs and tended to by their parents for a few weeks before they leave the nest. At this point, the male loses his feathers so that he is no longer able to fly and must tend to the chick for a few months, swimming around and teaching it how to fish. In order to begin this process, the chicks must jump from the cliffs, sometimes more than 100 feet in the air, into the water below to reunite with their fathers and begin. In case that’s not hard enough, glaucous gulls love to hang out by these cliffs and grab guillemot chicks out of the air before they reach the water. It’s a pretty gruesome side of nature and something we saw happen more than once in the hour or so we sailed along the cliffs. Arctic foxes also love to eat guillemot eggs.

Before this trip, I was worried that visiting the Arctic would be a serious downer. What better place to watch the planet die at 2x speed? Instead I saw something that is only becoming rarer; a sliver of an ecosystem that was actually relatively functional in one of the most vulnerable environments in the world. All the bears we saw looked fat and healthy. The ice was thicker than usual for that time of the season. The birds’ migratory patterns were more or less moving according to historical predictions and models. In this briefest glimpse of the region, things appeared to be functioning as they should.

Of course, that is in no way an accurate representation of what’s really going on. A good summer in Svalbard is not indicative of the region at large. At the history museum in Svalbard, an animated map projection shows the rapid recession of the ice over the last 50 years. This is not news to anyone who subscribes to basic facts, and you’ve probably seen something almost identical at some point, but it hits a little harder when you’re standing in the middle of this area and can look out the window and see dirt where there once was a glacier.

When you’re in the Arctic, it’s you that feels vulnerable. Seeing animals that are so adapted to such a harsh environment, you feel really small and ill-equipped to deal with the natural surroundings among animals that can seem invincible by comparison. It’s a humbling experience and a feeling that bears remembering, as the reality is that we are creating a world in which these animals will be vulnerable and largely unable to survive.

These animals and this part of the world is not the only ecosystem under threat, but the Polar regions are on the front lines. More so than anywhere else I’ve been, the Arctic really forced me to think about, in a very concrete way, how long this would all be here, and whether or not you will be able to see a wild polar bear in 10-20 years. I’m not sure anyone is immune to the incredible power of being able to experience such majestic wildlife up close and importantly, on its terms. We should remember how privileged we are to be able to live among such incredible sublimity.

After the Arctic, I headed to Copenhagen for a few days, which I covered already in my Scandinavian cities post. From there, I continued on to the Faroe Islands, a Danish archipelago in the far north Atlantic above the United Kingdom. More about those amazing islands in my next post.